Description

Iconic Images of a New Land

This article appeared in Israel’s Leading Newspaper. The article was written by veteran world known Noam Dvir.

The leading architectural photographer of the 20th century, Julius Shulman documented the work of American’s preeminent designers for 75 years. Largely forgotten until now, however, was a seminal trip to Israel in 1959, in which he captured in a moving way both urban and rural landscapes

Oct. 12, 2011

Four years ago Julius Shulman decided to sell his private archive to the Getty Center in Los Angeles, one of the most important museums and research centers in the art world. As the 20th century’s leading and most productive architectural photographer, Shulman (1910-2009 ) took some 70,000 pictures during his lifetime, many of them of canonical buildings, as well as of thousands of other private and public projects.

During a 75-year career Shulman worked closely with such prominent architects as Frank Lloyd Wright, Richard Neutra, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Charles and Ray Eames. Over time his photographs themselves became an integral part of the visual and cultural canon in the United States and worldwide.

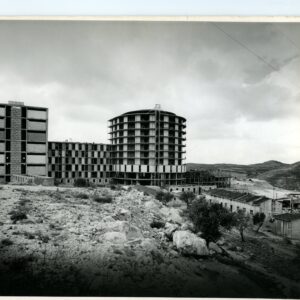

The administrative building on Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus.Credit: Julius Shulman, courtesy of the Getty Research Institute Archives

Research on Shulman is just beginning. The Getty Research Institute only recently completed the cataloging and storage of his archive (fortunately, Shulman was very organized ), and they are now working on digitalization, which will enable surfers from all over the world to access the collection from their computers. Already during the initial sorting process, a series of fascinating discoveries were found with respect to 20th-century architecture, as caught in Shulman’s lens. Among these were images from a previously unknown visit to the State of Israel in 1959. This article marks the first publication in Israel of photographs by Shulman.

Julius Shulman, who was born in Brooklyn to a Russian Jewish family, was the most faithful recorder of American Modernism. He arrived in Israel during one of the most interesting periods in terms of architecture, and photographed the country’s most interesting buildings: the Mann Auditorium and the Helena Rubinstein pavilion in Tel Aviv, the Hadassah University Hospital in Ein Kerem, the Hebrew University campus on Givat Ram in Jerusalem, the Churchill Auditorium at Haifa’s Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, row housing in Nazareth, Ichilov Hospital and the Land of Israel Museum in Tel Aviv, as well as the Dan Hotel on the Tel Aviv promenade, and the gravesite of Baron Edmund de Rothschild and his wife in Zichron Yaakov. He also photographed landscapes and smaller projects that reflected the development of Israeli society.

The first clue about Shulman’s long-forgotten visit to Israel was discovered by chance in the Israel Architecture Archive, among whose collections are many international publications related to 20th-century architecture in the Jewish state. In a tattered copy of the American magazine Progressive Architecture from February 1961, architect and historian Zvi Elhayani found a picture with a small credit to Shulman in an article about new hospitals, which among other things covered the construction of Hadassah University Hospital in Ein Kerem, designed by Joseph Neufeld, on the western edge of Jerusalem. From that point some careful detective work ensued, with the goal of discovering the details and results of that visit, with the help of Shulman’s family and researchers at the Getty Center, in addition to conversations with architects and professionals who met him in Israel .

The 1959 visit was apparently one of the most important professional experiences in Shulman’s career – one that reveals a profound connection to his Jewish identity that until now was considered marginal to the study of his work.

“I remember that when he returned from Israel he was very moved. As though he had been in a very special place,” said Judy McKee, Shulman’s daughter from his first marriage, in an interview with Haaretz a few weeks ago. “It seemed to him like an entirely different world – very new but ancient at the same time. He felt that Israel was a tabula rasa for the growth of a new architecture. Everything seemed so optimistic to him, and focused on the future. He was very moved by it and spoke a lot about the wonderful people he had met.”

Shulman arrived in Israel on March 1, 1959, and remained until March 12. His travel expenses, or at least most of them, were underwitten by a stone-and-limestone quarry in the Zichron Yaakov area, owned by the Gilbert-Rothschild investment company. Some of the biggest manufacturers in the United States used his services regularly and published ads with his photographs in various magazines.

During his stay here, Shulman met the leading architects of the period: Ze’ev Rechter and his son Yaakov Rechter, Dov Carmi, Zvi Meltzer, Arieh Sharon, Benjamin Idelson, Yosef Werner Witkover and many others. They introduced him to their work. “In many cases he would travel to a certain assignment and then he would make friends with people and find other projects,” added McKee.

Under the influence of the visit, Shulman even published a unique document in the American magazine Architectural Forum: a three-page personal photography journal called “Israel: A Photographer’s Notebook,” in which he gave his impressions of the buildings he photographed and the landscapes he encountered.

In an introduction to the article, the magazine explained that: “Architectural photographer Julius Shulman went to Israel early this spring to do some promotional photography. He stayed on to take a ten-day photographer’s holiday around the country and among its architecture. Shulman found that Israeli architects’ leading problems are too little water, too much sun and no vital architectural tradition. Yet he noted a fresh design-consciousness and was constantly amazed by the changing landscape. In a desert scene he would unexpectedly come upon an urbane public building, like the Tel Aviv Municipal Hospital; on a slope he would find row houses for new immigrants, like the housing at Nazareth; and everywhere, a new environment in the making”.

“Julius photographed several hundred pictures in Israel, and judging by his choices, it’s clear that he was well aware of what he was photographing,” said Anne Blecksmith, a senior librarian at the Getty Center, who was in charge of the cataloging and documentation of his archive over a period of about five years. “What’s interesting is that in Israel Julius met architects who had studied at the Bauhaus and developed a language that was very similar to what he was familiar with from California.”

Blecksmith confirms that he was very excited about the new architecture of the new state, and his visit was of great personal significance for him: “He traveled around the world a lot, but this is one of his most productive trips in terms of work. He took it very personally and printed hundreds of pictures of it. When something really interested him he wrote some text about it, but the publication of a personal photography journal is very unusual.”

Shulman’s enthusiasm for Israel is definitely in evidence in his pictures – for example, in the series of photographs of the Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus. Its construction began in 1953 as part of the new government complex, and was designed in a clearly formal Modernist style. Although the master plan was drawn up by Richard Kauffman, Joseph Klarwein and Heinz Rau, the individual buildings themselves were designed by young architects from the so-called 1948 generation, who surprisingly received recognition and a full embrace from the establishment. On the campus, Shulman encountered the ceremonial entrance square of the Jewish National and University Library, and the buildings housing the faculty of humanities and social sciences, which had all been dedicated only two or three years before his visit, but he chose to focus on the administration building (designed by Dov Karmi, Zvi Meltzer and Ram Karmi ), a kind of rectangular box that stands on a low elongated structure with colonnades.

In the most iconic photograph – of the sort that epitomizes the atmosphere the TV show “Mad Men” (about American advertising in the 1950s ) tries to conjure up – an elegant woman wearing a head scarf is seen walking along a glassed-in corridor, through which the building is visible. This is a symphony of lines, looks and movement: The rigid facade is contrasted with the diagonal lines of the corridor space and the movement of the woman. All of this is delicately reflected in a pool of water in an inner courtyard – including the clouds that approach from behind. Shulman left nothing to chance and staged all his photographs up to the last detail. The woman certainly didn’t pass there by accident, and it is possible that had he been capable of doing so, he would even have staged the movement of the clouds and the sun in the sky. In his photographic essay in Architectural Forum, he wrote that the new buildings of the Hebrew University were gathered around a landscape element that is full of life: a pool of water.

In another iconic picture of the university, which is very reminiscent of photos he took in California, Shulman photographed the bus stop at the entrance to the campus, which was designed by Avraham Yaski and Amnon Alexandroni. It’s an impressive concrete pavilion characterized by delicate details and artwork done in unrefined stone, designed by sculptor Yitzhak Danziger. Shulman chose to emphasize the structure’s hovering quality and feeling of lightness. The strong Israeli sun is broadly expressed in the picture by means of the play of light and shadow on the architectural elements.

In almost all the pictures Shulman took in Israel one can see a strong contrast between the primeval landscape and the Modernist architecture. For example, in an amusing photograph of the first structure of Tel Aviv’s Ichilov Hospital (by Sharon and Idelson ). The building, located at the corner of Weizmann and Dafna streets, is today concealed by the cumbersome new Sami Ofer Heart Center building, but in 1959 the area around it was totally empty. In the forefront of Shulman’s picture, a cow is grazing.

‘A people person’

Several of the most moving photographs in the 1959 series are not necessarily buildings, but rather urban or natural environments. For example, housing projects being constructed in Ashkelon, Bedouin and sheep in the Negev, or a lovely photo of Haifa Bay from the top of Mount Carmel, in which the landscape is framed by a pine tree with needles and twisted branches. In the background one can distinguish boats in Haifa Port and the sandy beach of the bay.

A special relationship developed between Shulman – who was “a people person,” as his daughter puts it – and architect Dov Karmi. The two spent a substantial part of his visit to Israel together, and Karmi took him to both large and small projects. Karmi introduced him to members of the Hordes family, for whom he went on to design a house in Herzliya (which also was featured later in Progressive Architecture ) and showed him the Bar-Shira House, a luxurious apartment house that was under construction on Ben-Gurion Boulevard in Tel Aviv. He also took Shulman to the Mann Auditorium in Tel Aviv and to the nearby Helena Rubinstein pavilion.

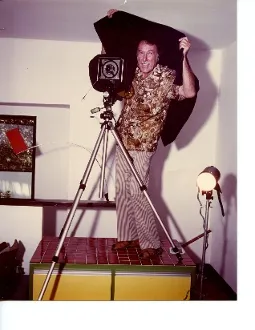

The two also toured around the country, a journey that included a visit to ancient sites. Work No. 2790 in the Getty archives collection includes photos from that excursion, including portraits of Shulman himself (“He liked to be photographed,” adds his daughter ) and an informal portrait of Karmi. He chose to photograph members of the Hordes family in several situations that are reminiscent of the life of comfort and leisure in the American suburbs back then – children playing on a lawn or a perfect family scene in the living room.

Newsweek once wrote that Shulman’s photographs were such a perfect reflection of the suburban lifestyle in the postwar years “that one can hear the voice of Frank Sinatra in the background hovering in the air and the sound of the ice cubes rattling in the transparent cocktail glasses.” In Israel it was apparently the radio that was playing, with music by Shimon Yisraeli and a “shpritz” drink.

Although Shulman often visited Mexico, South America, Asia and Europe, there is a particularly large quantity of pictures and unique personal accounts from his visit to Israel.

“In his pictures one can see very great excitement and sensitivity about the place,” adds Blecksmith. “For example, in the pictures from the Rothschild gravesite in Zichron Yaakov, one can sense that he experienced a strong connection between the surroundings on the one hand, and his camera and soul on the other.”

According to his daughter Judy McKee, Shulman was not particularly attached to his Jewish identity. “He may have had a bar mitzvah, but he saw God in nature,” as she puts it.

But according to Sam (Shmulik ) Heller, a relative who was in contact with him for many years, Shulman actually did have a unique connection both to Judaism and to Israel. Heller’s family fled from Austria after the rise of the Nazis. His parents immigrated to Israel and served in the right-wing Etzel (Irgun ) underground forces in Palestine, while his father’s brother and his wife immigrated to New York. Heller’s Aunt Olga met Shulman in the early 1970s, shortly after both had lost their spouses. They married in 1976 and lived in California.

“There was no blood tie between me and My aunt Olga, but we had lost everyone in our family and all we had left was one another,” the Ramat Gan-born Heller explains. “As a result Julius and I developed a special relationship. He used to like to talk a lot and you could sit with him for 10 hours and hear only stories from him. He was familiar with lots of people and lots of places and was very curious to know and learn about new things.”

Heller, who today works in real estate in the Los Angeles area, recalls that Shulman spoke a lot about his visit to Israel, and he believes that Olga – who experienced the trauma of the rise of the Nazis before escaping from Vienna- greatly strengthened his connection to Judaism.

Heller: “In the late 1950s everyone in America loved Israel and everyone wanted to help it. Julius was very enthusiastic about his visit there and was moved by the people who were working to build a good country for themselves. I don’t think he was a Zionist, but it definitely changed his attitude toward his Judaism.

“In the United States you can’t escape your Judaism, and wherever Julius went they would see him first as a Jew and then as a photographer,” he adds. “Why? Because he both looked and talked like a Jew. He may never have discussed his Judaism, but that doesn’t mean that it didn’t exist. I remember that a few years ago we mentioned that he was 97 years old, and he remembered the entire Kaddish prayer and even part of his haftara [the chapter from the Prophets he recited at his bar mitzvah]. I asked him – how is it that you haven’t forgotten? and he replied that he couldn’t forget it.”

Did you hear any details from him about the trip to Israel or significant experiences?

Heller laughs: “The problem with Julius was that he talked about himself so much that it was hard even to get a question in. I regret not asking more. I didn’t think he’d ever die.”

“The discovery of Shulman’s work in Israel enables a glimpse in real time at the change in the Israeli space a decade after its establishment,” says architect and historian Zvi Elhayani. “These were years when architecture, and culture in general, tried to connect the Modernist zeitgeist with the sensitive spirit of the place. As opposed to Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini, who visited Israel in 1963 and was disappointed to discover the accelerated development at the cost of the primeval landscape – Shulman came for the purpose of commercial documentation of that development. Not only the architecture of relatively expensive public buildings, but the construction of new cities and the housing projects, too.”

Elhayani emphasizes, however, that Shulman came on a specific commercial assignment , and that during the 10 days of his visit he was accompanied by a hegemonic retinue of leading local architects “who showed him what they wanted to show him.”

“It would be interesting,” adds Elhayani, “to examine the entire corpus of Shulman’s work in Israel and to see whether, in addition to his excitement about making the wilderness bloom, about the unique architectural language of Israeli architects or their impressive solutions of shade and ventilation – he cast an eye on the marginalized population: the transit camps, the ‘non-architectural’ housing solutions and the vestiges of Palestinian space. All those were present in full force during Shulman’s visit.”

“There’s a lot to say about Julius Shulman, he was a very complex person,” concludes Anne Blecksmith. “We talk a lot about the architecture he photographed, but we sometimes forget that he was the one who staged it. He isn’t a sidekick in this story, he’s a major player. I think that recently people have been showing increasing interest in the way he caught the built-up environment in the closest and most personal way.”